Using the Swiss National Bank (SNB) as an example, this advanced text explains which objectives are pursued by monetary policy, how monetary policy is implemented and how the economy is influenced in the process. In general, central banks in other countries or currency areas conduct monetary policy in a similar way.

As Switzerland’s central bank, the Swiss National Bank is tasked under the Federal Constitution with pursuing a monetary policy that serves the overall interests of the country. Its mandate is explained in detail in the National Bank Act: The SNB’s primary objective is to ensure price stability, while taking due account of economic developments.

The SNB considers prices to be stable if inflation is less than 2% per year in the medium term. Inflation is measured using the consumer price index (CPI), which records the average price level of consumer goods for private households. As long as this level does not rise by more than 2% annually, the objective of stable prices is considered to have been met. However, if prices increase by more than 2% (inflation) or decrease steadily (deflation) over the long term, this would lead to undesirably large changes in the purchasing power of money. Sustained deflation thus also misses the objective of price stability.

Price stability is an important prerequisite for economic growth and prosperity, while inflation and deflation impair economic development. If the purchasing power of money were to fluctuate constantly, households and businesses would find it difficult to plan reliably, leading to poor decisions in the use of labour and capital as well as a redistribution of income and wealth. In the event of sustained inflation, lower-income households experience a significant loss of purchasing power on their savings, whereas the wealthier are better able to protect themselves from the negative effects of inflation through targeted investment.

In pursuing its objective of price stability, the SNB must take due account of economic developments. This means that a country’s economy should neither be allowed to overheat nor contract significantly. This type of stable environment is characterised by sustainable economic growth and low unemployment. In general, there is no conflict between the objectives of price stability and economic development. Since strong price rises are often caused by the economy overheating, monetary policy can address both issues at the same time. If objectives do conflict, however, the SNB must prioritise the overall interests of the Swiss economy, where price stability always takes precedence.

Before a central bank reaches a monetary policy decision, it first analyses inflation developments and the economic situation at home and abroad. It assesses future economic developments and prepares an inflation forecast. This comprehensive analysis is used as the basis for deciding whether monetary policy needs to be adjusted. If expected inflation and economic developments deviate from the objectives, action is required. Chart 1 shows the key aspects of the monetary policy decision-making process.

The monetary policy decision always consists of a key interest rate decision. The key interest rate level and any changes to it provide information about the monetary policy course being pursued by a central bank. The central bank uses its key interest rate decision to influence monetary conditions, i.e. interest rate levels and exchange rates.

A key interest rate increase prevents the economy from overheating and inflation from rising too sharply. By adopting such a restrictive monetary policy, the central bank is applying the brakes, or tightening monetary conditions. By contrast, a key interest rate cut aims to avoid deflation and stop the economy from sliding into recession. With this sort of expansionary monetary policy, the central bank is stepping on the gas, or easing monetary conditions.

In addition to its interest rate decision, a central bank can also take other monetary policy measures to change monetary conditions. Ultimately, the aim of monetary policy decisions is to create monetary conditions that prevent extreme fluctuations in inflation and the economy.

In Switzerland, the SNB generally conducts a monetary policy assessment every quarter. It prepares a conditional inflation forecast, which serves as the basis for its monetary policy decision. The forecast provides information about the anticipated path of inflation, based on the assumption that the key interest rate announced at the time of publishing will remain constant over the next three years. In this way, the SNB shows how it expects consumer prices to move in the event that monetary policy does not change.

The conditional inflation forecast is also a key element in communication. It helps to gauge the need for monetary policy action in the future. If the forecast puts inflation for the medium term outside the price stability range of 0% to 2% per year, an adjustment to monetary policy can be expected.

(The latest conditional inflation forecast can be found at SNB data portal.)

Central banks generally implement their monetary policy by setting a key interest rate, or policy rate. This is considered the conventional way to conduct monetary policy, where economic developments and inflation are influenced and steered using interest rates.

Since the financial crisis, central banks have also deployed other monetary policy instruments to pursue their objectives. Such unconventional measures have helped to ensure appropriate monetary conditions over time.

In Switzerland, the SNB pursues its monetary policy objectives by setting the SNB policy rate. This rate indicates the interest rate level that the SNB targets for short-term secured money market rates. The most representative of these money market rates is SARON (Swiss Average Rate Overnight). This is the interest rate at which commercial banks lend each other money on a short-term basis (overnight), against collateral such as government bonds. The SNB seeks to keep SARON close to its policy rate at all times, and can do so by being active directly in the money market.

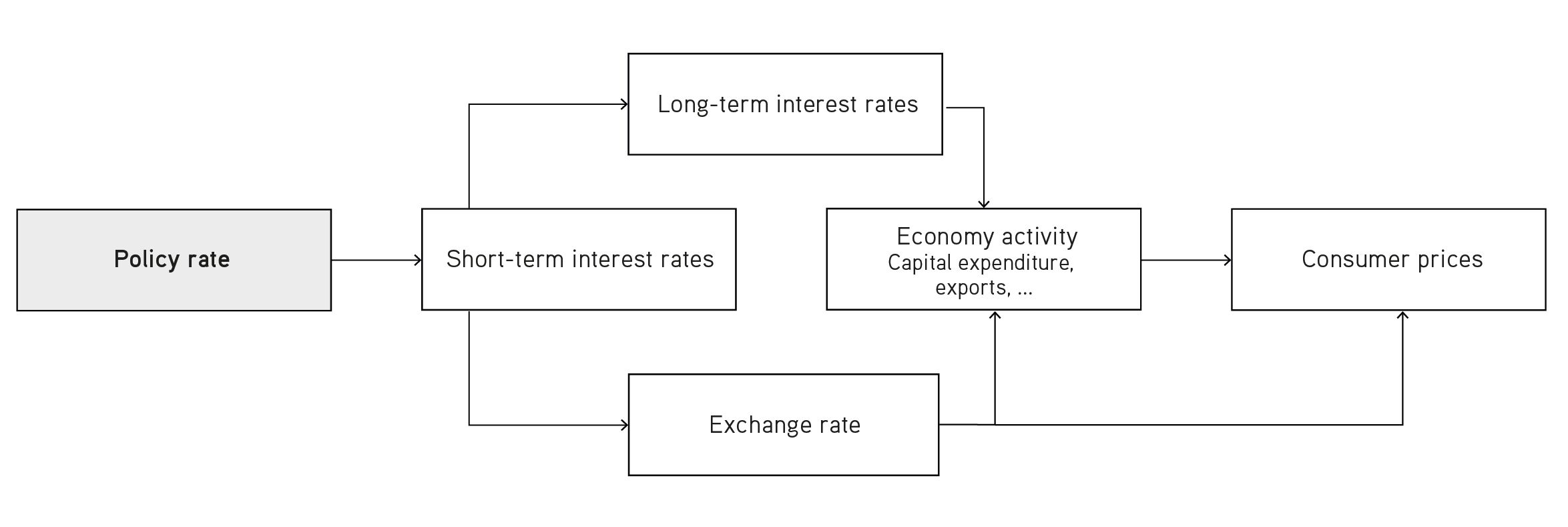

Chart 2 shows the transmission mechanism of monetary policy. The central bank uses its policy rate and money market activities to steer short-term interest rates, such as those for short-term credit transactions. Monetary policy is subsequently transmitted to the economy via other channels.

The upper path in chart 2 illustrates how an interest rate change affects lending, and is referred to as the credit channel.

When a central banks raises its policy rate, it triggers a sort of chain reaction that pushes up the general level of interest rates, i.e. the cost of borrowing in the economy. Not only do short-term loans become more expensive, but the cost of long-term loans and yields on bonds also increase. Long-term interest rates rise. For homeowners, this means higher mortgage rates; for companies, higher capital costs for loans. Overall, there is a drop in investment and consumption, not least because the higher interest rates make saving more attractive. This curbs aggregate demand for goods and services. With companies no longer able to sell their products as well as before, they refrain from raising prices and wages. As a result, inflation slows.

When a central bank lowers its policy rate, its monetary policy has the opposite effect. The cost of borrowing declines, which in turn stimulates the economy and fuels inflation.

The lower path in chart 2 shows how an interest rate change affects the exchange rate and foreign trade, and is referred to as the exchange rate channel. For a country like Switzerland, which has an economy with strong international integration and a currency of global significance, the exchange rate channel plays an important role.

When the policy rate is raised, the Swiss franc gains in value. This is because higher interest rates in Switzerland make investments in the country’s own currency more attractive. More investors exchange foreign currency for Swiss francs, increasing demand and thus pushing up the value of the franc. Due to the appreciation of the Swiss franc, exports become more expensive, while imports become cheaper for Swiss households and companies. The decline in demand for Swiss goods and services (lower exports, higher imports) has a dampening effect on the Swiss economy and, ultimately, also on inflation.

In the case of a policy rate cut, Swiss franc investments become less attractive and the currency loses value. This boosts Swiss exports and thus too the domestic economy. However, a depreciation of the Swiss franc also means that it costs more to buy foreign currency, making imports more expensive. Both of these effects result in an increase in inflation.

In an environment where interest rates are already very low, the option of steering short-term interest rates reaches its limit. There are limits to the extent that a central bank can lower interest rates, and with a policy rate of zero, monetary policy is no longer conventional as described above. Nevertheless, even when money market rates are low, a central bank still has a range of tools at its disposal to help achieve its goals, namely by attempting to directly influence not only short-term, but also long-term interest rates and the exchange rate. These are referred to as unconventional monetary policy measures.

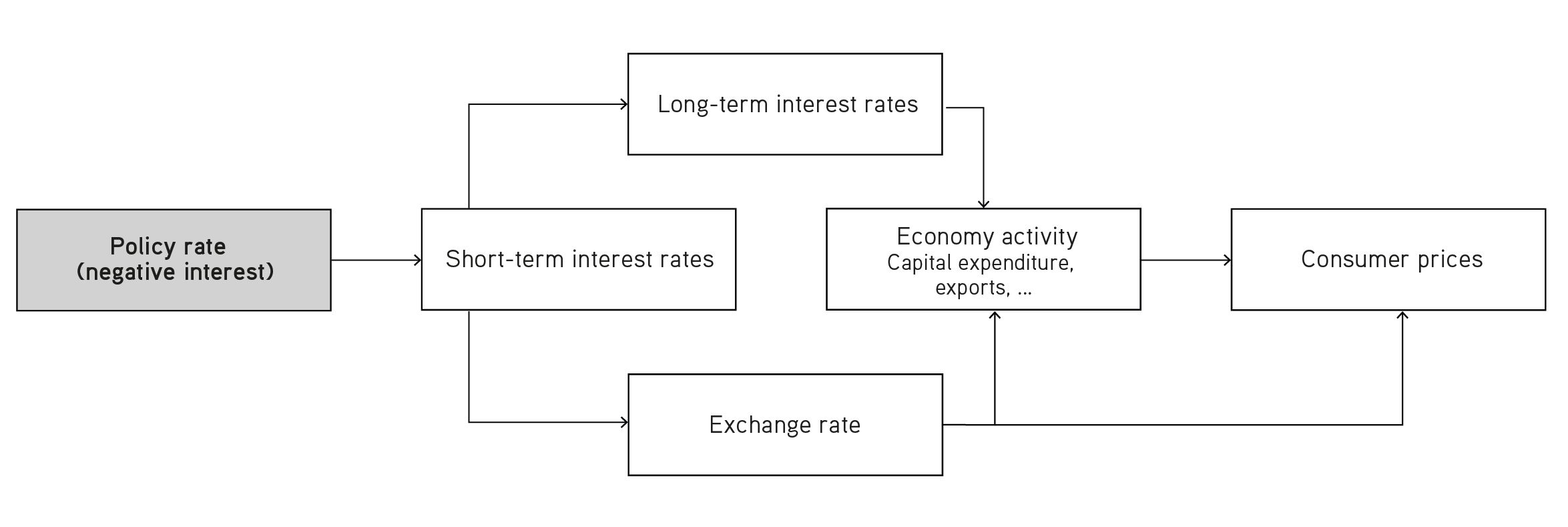

Even if there are limits when it comes to lowering interest rates, negative interest rates are certainly a possibility. Should this be the case, interest would not be credited to the account, but debited. In the event of strongly negative interest rates, households and companies would be less likely to leave their credit balances in their accounts, but would instead switch to cash in order to avoid losses. However, slightly negative interest rates are acceptable, as holding large amounts of cash incurs costs, for example for secure storage in a vault. Experience has shown that the transmission of monetary policy via the credit and exchange rate channels can also work with negative interest rates (chart 3).

In December 2014, the SNB announced the introduction of such a negative interest rate, and set it at –0.75% in January 2015. Its aim was to reduce the attractiveness of the Swiss franc. Since the financial crisis of 2007/2008, the Swiss franc had repeatedly been a sought-after currency among investors from Switzerland and abroad. Demand for the franc was correspondingly high, and it gained in value as a result. However, a strong appreciation of the Swiss franc weighs on the export economy, dampens economic activity and increases the risk of deflation. With negative interest, the SNB aimed to counter this appreciation and the associated consequences.

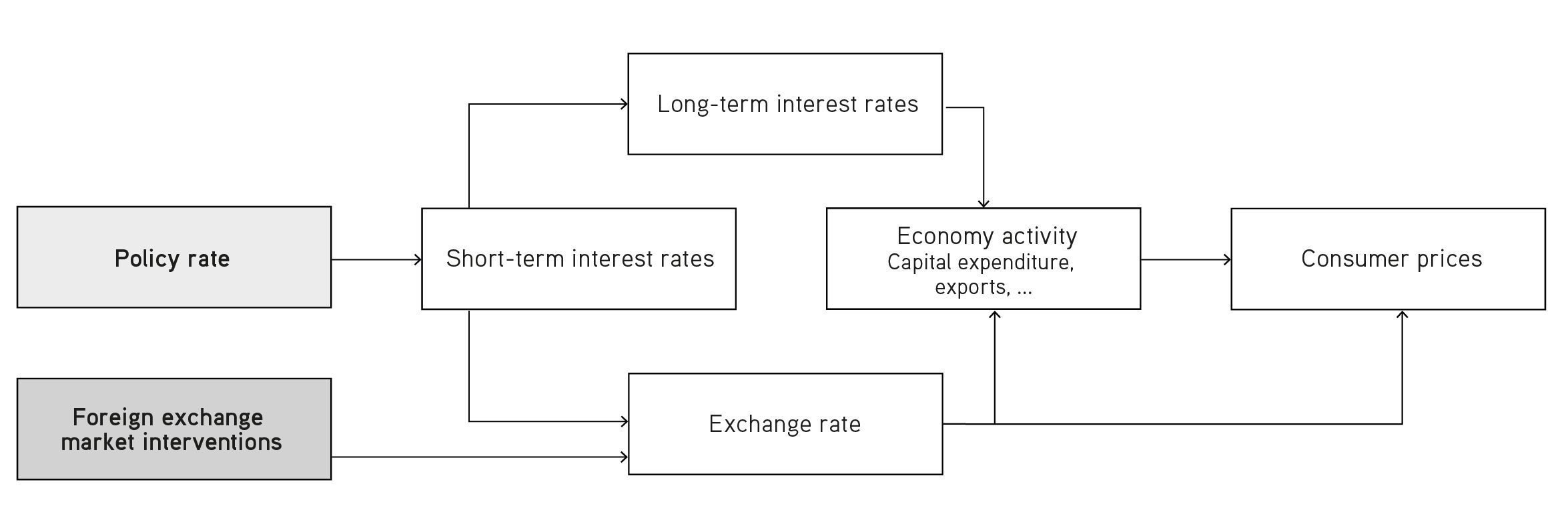

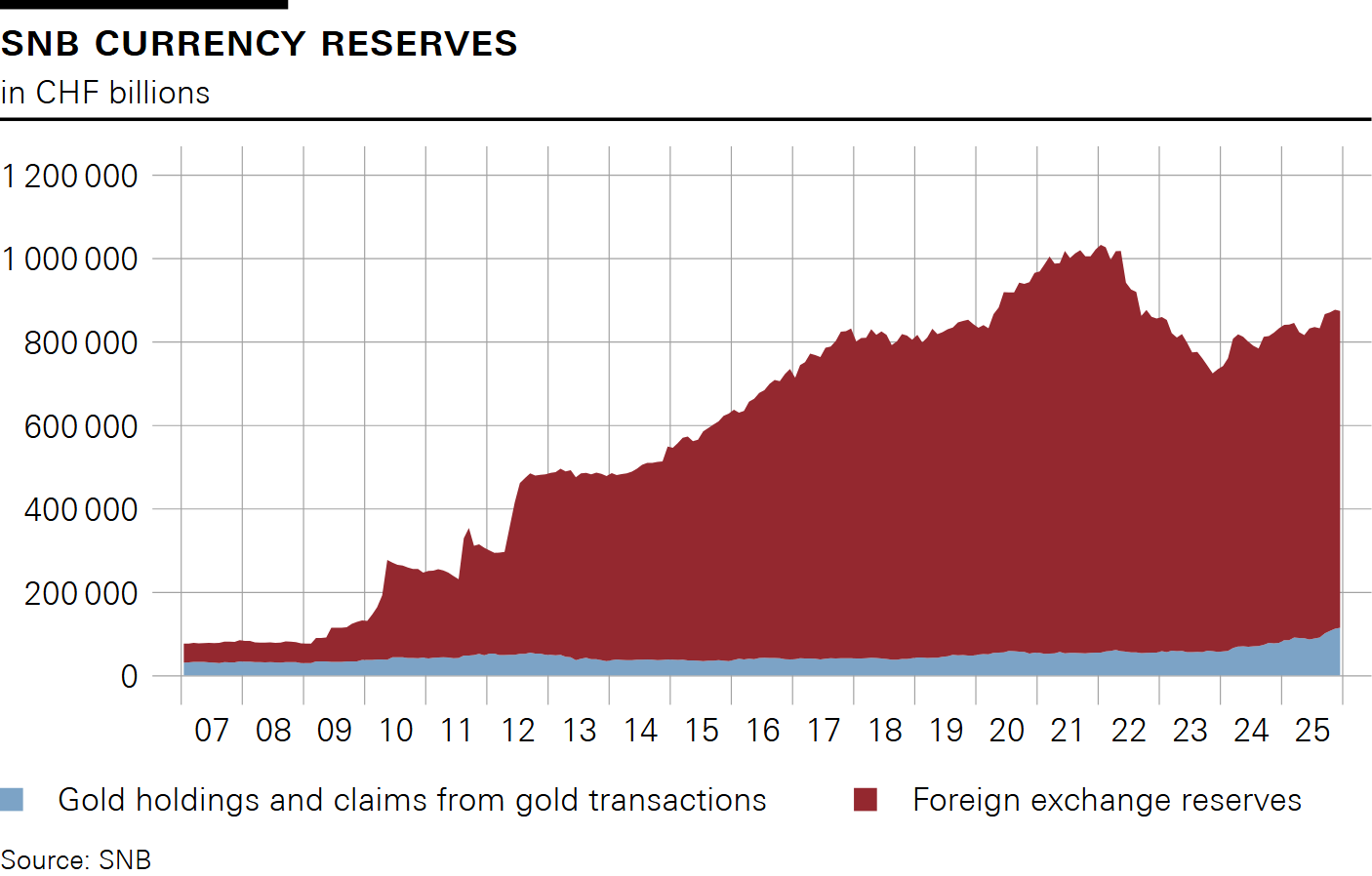

Foreign exchange market interventions are also considered unconventional measures. The SNB purchased foreign currency against Swiss francs on a number of occasions, namely after the financial crisis of 2007/2008, following the onset of the euro area debt crisis in 2010 and during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. As with the negative interest, the aim was to counter the appreciation of the Swiss franc. When the SNB buys foreign currency, it drives up demand for other currencies, and the Swiss franc weakens accordingly. In this way, it directly influences the exchange rate and reinforces the monetary policy impact on the economy and inflation via the exchange rate channel (chart 4).

In 2011, the Swiss franc appreciated swiftly and steeply, as many investors regarded it as a ‘safe haven’ compared to other currencies in the context of the crises at the time. To counteract this development, the SNB set a minimum exchange rate of CHF 1.20 per euro in September 2011, which was a considerable intervention in the foreign exchange market. In order to enforce this rate, the SNB had to purchase large quantities of foreign currency. It thereby supported the Swiss economy and ultimately ensured price stability. In January 2015, the SNB discontinued the minimum exchange rate, whereupon the Swiss franc appreciated abruptly. Negative interest, which was introduced at almost the same time, was partially able to counter the upward pressure on the Swiss franc.

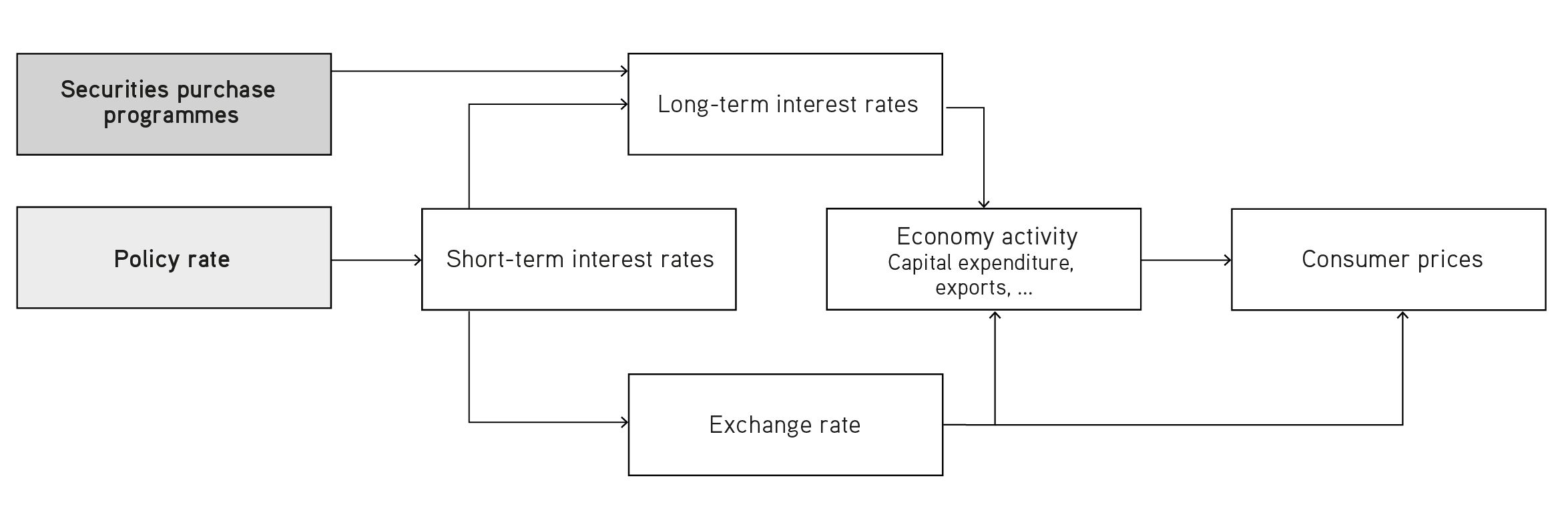

Securities purchase programmes are considered unconventional measures as well. The central bank may, for example, seek to keep the financing costs of long-term projects low in order to stimulate economic growth. In this case, it purchases longer-term assets, such as government bonds, directly in the capital markets. This enables it to reduce long-term interest rates and reinforce the effect via the credit channel (chart 5).

In addition, the central bank can influence the expectations of the markets and the public regarding the future development of short-term interest rates by announcing its intention to keep the policy rate low in the long term (forward guidance). Provided that the financial markets and the public consider such an announcement to be credible, it has an impact on long-term interest rates.

Certain factors make monetary policy implementation either easier or more difficult.

It may take some time before a central bank’s monetary policy decisions take effect. This applies in particular to the credit channel. Changes to short-term interest rates may take two to three years to feed through to a country’s prices. To take this sluggish response into account, the central bank takes a forward-looking approach when formulating its monetary policy and preparing multi-year forecasts on future economic and inflation developments. If it waited until inflation rose or fell before reacting, it would be too late.

The effect that monetary policy has on the economy is only ever temporary. The long-term growth of a country’s economy (so-called trend growth) depends on other factors, notably the size of the working population, education level, physical capital, technological progress and institutional quality. In other words, the stimulating effect of an interest rate cut on the economy evaporates after a certain length of time. All that remains is a higher price level. For this reason, the primary objective of monetary policy is not growth, but rather ensuring price stability, which can be effectively influenced in the long term.

The effect of monetary policy measures on inflation depends on the utilisation of economic capacity and thus on the economic activity. During a recession, a central bank can lower interest rates and thereby stimulate demand without this causing prices to increase immediately across the board. The reason being that in an underutilised economy – with high unemployment, empty order books and underutilised production capacities – inflationary pressure is low. If, however, interest rates are lowered while economic capacity is well utilised, consumer prices tend to rise much more rapidly.

Well-anchored inflation expectations within the range of price stability facilitate the implementation of monetary policy. It is possible that inflation might rise sharply in the short term or that deflation could result from a sudden recession. However, if households and companies expect the central bank to continue to meet its predefined inflation target in the future, they are less likely to react when inflation deviates temporarily from this target level. The more stable inflation expectations are, the easier it is for a central bank to keep inflation in check despite temporary fluctuations.

The economic recovery after the COVID-19 pandemic and the war between Russia and Ukraine resulted in a global surge in inflation that fundamentally changed the monetary policy situation.

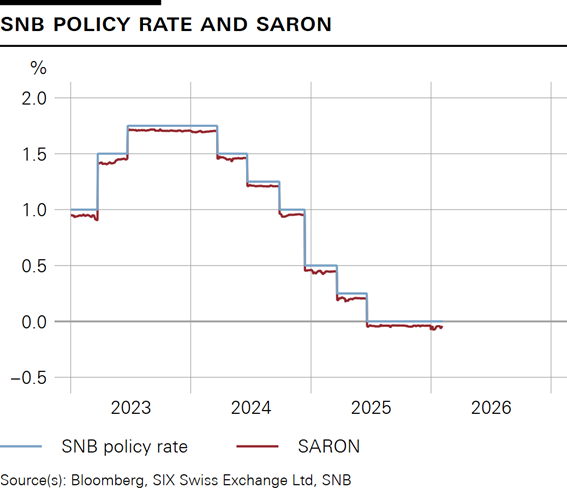

In June 2022, after almost eight years of negative interest, the SNB raised its policy rate for the first time. In 2022 and 2023, it tightened its monetary policy further, bringing the policy rate up to 1.75%. With these policy rate increases, the SNB aimed to counter increased inflationary pressure. As this pressure eased significantly towards the end of 2023, the SNB began to relax its monetary policy from 2024 onwards and lowered its policy rate. Chart 6 shows the development of the SNB policy rate and SARON since 2022, when interest rates were steered from negative to positive territory.

(The current level of the SNB policy rate can be found on the SNB website under Current interest rates and exchange rates.)

Besides setting the policy rate, the SNB may, if necessary, continue to use additional monetary policy measures to influence the exchange rate or interest rate level. This includes the foreign currency sales in the context of the foreign exchange market interventions after the COVID-19 pandemic. Chart 7 shows how foreign exchange reserves have declined since the beginning of 2022.

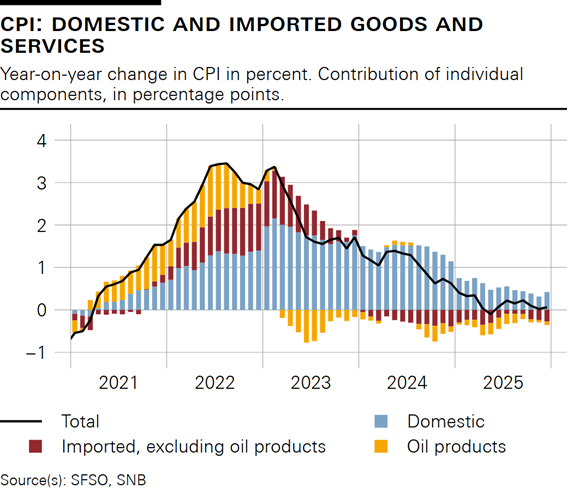

By selling foreign currency, the SNB was able to support the appreciation of the Swiss franc, which helped to curb imported inflation. Chart 8 shows that the contribution to inflation from foreign goods and services (red bars) decreased over the course of 2023. Imported oil products also became cheaper, at least partially due to exchange rate movements. The appreciation of the Swiss franc thus prevented inflation from being fully transferred from abroad, consequently slowing inflation in Switzerland.

The developments since 2022 show how the SNB has adapted its monetary policy to the positive interest rate environment and is seeking to ensure appropriate monetary conditions for the Swiss economy. Its objective remains ensuring price stability while taking due account of economic developments.