Ensuring price stability is one of the fundamental tasks of a central bank. But combating excessively high inflation can incur substantial costs. A good example is the situation in Switzerland in the 1990s.

Stable prices are an important condition for growth and prosperity. But the market value for goods and services can change anytime. If the prices of individual products rise or fall, the overall economic impact is small. But if the prices for a broad range of goods increase, money loses its value. This is called inflation.

A lasting increase in the general price level reduces the purchasing power of money. The same amount of money now buys you less. This is especially the case when the money supply grows faster than the volume of goods in the overall economy. The demand for goods exceeds the supply of goods, which leads to an increase in prices in general and fuels inflation.

To maintain the purchasing power of money, every central bank has the aim of keeping prices in its economy as stable as possible. Excessive inflation can be combatted with restrictive monetary policy. Put simply, the central bank increases its policy rate and thus reduces the money supply in circulation. If the volume of goods remains the same, the value of money thus rises and inflation sinks.

However, a policy rate being increased over a longer period of time can severely slow down a country’s economic activity. A historical example from Switzerland illustrates this:

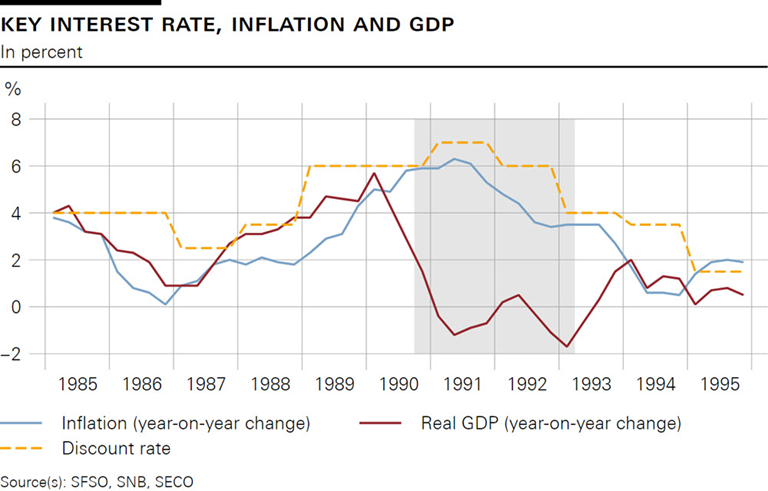

In October 1987 the US stock market experiences its biggest crash since World War II. Because Switzerland is also affected by this ‘Black Monday’, the Swiss National Bank (SNB) subsequently floods the markets with money to counteract a collapse of the real economy. It lowers its key interest rate at the time, the ‘discount rate’, from 4% to 2.5% within one year and thereby stimulates economic growth.

The SNB’s expansionary monetary policy is accompanied by increased interest in the real estate market. First, after the stock market crash, investors are looking for alternative investment opportunities. Second, low interest rates paired with rising income levels are stimulating demand for residential and commercial real estate. Consequently, the banks relax their lending policies and make the necessary financial resources available.

These circumstances lead to a veritable boom in the Swiss economy from 1987 onwards.

The growth of the gross domestic product (GDP for short) accelerates up to 5.7% at the beginning of the 1990s. The uncomfortable side effect – in these same years inflation picks up as well and increasingly gets out of hand. The SNB therefore begins to gradually raise its interest rates from 1988. With the goal of restoring price stability, it raises the discount rate to a record high of 7% in the span of three years.

The drastic reaction of the central bank seems to show results – the reduced supply of money leads to inflation sinking below 1% in the mid-1990s. But, once again, there is an uncomfortable drawback. The persistently high interest rates hamper economic activity and economic growth collapses. Switzerland slides into a recession which will last for around two and a half years.

The recession is further intensified by a real estate crisis at the beginning of the 1990s. Fuelled by the low interest rate policy of the central bank, the relaxed lending policies of the banks, and the speculation on the housing market, a real estate price bubble grows until the end of the 1980s, when it finally pops. Aside from the fiscal policy measures, the biggest contribution to the price collapse comes from the interest rate hikes by the SNB.

Since a significant part of their credit portfolios consist of real estate, many banks feel compelled to tighten their lending conditions. Construction, which is largely funded by bank loans, suffers in particular. Declining construction and sudden lack of capital lead to overcapacities and a wave of insolvency procedures.

The SNB’s fight against inflation also causes a string of economic costs that are typically associated with a recession.

Sinking investments – The banks’ more restrictive lending policies and the higher interest rate level make it more expensive for companies to borrow money. At the discount rate’s peak in 1991, gross capital formation (formerly 'gross domestic investment') sees a severe downturn of –8.6% (compared with 12.7% growth in the previous year).

Curbed consumption – The falling real estate prices lead to big value losses for many real estate owners, which has a negative impact on their wealth. They also suffer from the higher mortgage rates, as they have less income available after repaying their loans. Both of these factors slow the growth of household consumption for several years.

Rising unemployment – In 1994, unemployment rises to almost 5% – the highest value recorded to date. The main factor, in addition to the restrained consumption and investment activity, is the weakening global economy. The volume of exports – on which Switzerland is dependent due to its strong outward orientation – is correspondingly lower.

In summary, the SNB’s restrictive monetary policy negatively affects aggregate demand. This development is also reflected in the real GDP, which only returns to an upward trajectory from mid-1993.

In hindsight, it is apparent that the rapid increase in inflation from 1989 was mainly slowed by the SNB substantially raising its main monetary policy instrument at the time, the discount rate, for an extended period of time. In the context of a protracted recession, however, it also incurred criticism for hamstringing the already weak economy. This approach was nevertheless necessary to regain price stability and thus the credibility of the central bank.

To this day, the consistent fight against inflation is an important pillar of the monetary policy strategies of central banks around the world. Especially for private households, unstable prices can have profound implications and increase inequalities.

Low-income groups of people such as those in low-wage jobs, pensioners or the unemployed are hit the hardest. They cannot simply adjust their income level to the generally increasing price level. Because these groups tend to spend a substantial proportion of their disposable income on day-to-day goods, greater expenditure for food, housing and energy has a particularly severe impact.

At the same time, inflation puts strain on the employed. Their wages are often fixed over a certain period in wage negotiations or mutual agreements. Rising prices reduce the purchasing power of their salary, because it is only adjusted with delay.

To protect the economic participants and maintain the value of money over time, central banks continue to focus on price stability.